by Rachel Phipps

To what lengths should we go to make sure the meat and animal products we consume meet our exacting quality, welfare, and environmental standards? Our writer pays a visit to Longland Farm in Kent, England to see if their promise of high-quality, field-reared, low environmental impact birds is all that is cracked up to be.

———

It started with a discussion with another food obsessive about where we could get local, high-welfare duck. Pork, beef, chicken, and lamb are available in abundance, but it was not until we spied on Instagram locally reared duck in a dish posted by a nearby Michelin-starred chef did we discover that, since 2018, field-raised ducks, geese, chickens, and turkeys had been available right under our nose.

For a long time my argument has been that you don’t have to cut out meat and animal products entirely to be kinder to the environment; if everyone does their bit, for example eating much less, better meat, reared with an eye to lowering the environmental impact of farming we can still be part of the change. So, on discovering a farm that supplies birds to some of the country's top restaurants literally right up the road, I decided to pop along to find out if their promise of high quality, high welfare, low environmental impact birds that don't travel to slaughter, who don't live their entire lives inside and who are not allowed to wear out the fields they live in was all that it was cracked up to be.

Are we really told the truth about the meat that we are eating?

Instagram is a big part of the business at Longland Farm, and not just because it helps social media-obsessed journalists like me find them. Whilst most of the geese they rear go to locals for their Christmas table (happily helping contribute to lower carbon footprint festive dinners), aside from a few farm gate purchases and supplies in local butchers almost all their business comes from the restaurant industry. I was surprised to hear that this was not done through a specialist supplier, but that they deal with all the restaurants who come to them via word of mouth - because they’ve seen other chefs using Longland duck, often on social media - themselves. Provenance is always important, so it was heartening to hear that pretty much every single restaurant they supply has visited the farm; with so many false phrases being used to pretend something is ‘free range’ or ‘farm reared’ on supermarket packaging, chefs and restauranteurs want to make sure the stories behind their menus are true.

‘Fake free-range’ was a topic we alighted on pretty quickly almost as soon as I’d arrived; against a retail backdrop where clever wording is now regularly employed to try and convince the consumer that barn-raised birds are indeed free-range, for example, even my just standing there on the farm looking around, for me, made a strong case for taking the initiative to source what I’m going to be eating for dinner myself: just like those restaurant chefs, don’t you want to be sure that the narrative behind your meal is not a false one?

My first visit to Longland Farm last Christmas on goose collection duty gave me a very good impression of what they were about before I’d even met the husband and wife team - Giles and Kate - behind the operation. I’m still surprised that the business is only four years old; and even then they only had two years prior farming experience under their belts, coming from busy, fast-paced, and mentally exhausting lives as a business consultant and National Health Service specialist, respectively.

As we drove into their yard we had to dodge the (truly free-range!) hens and the odd ornamental rare breed duck. A local man offering knife sharpening had set himself up next to the collection point, making it clear that Longland is a farm firmly rooted in the community: since the start of the pandemic they’ve given over 300,000 eggs away at the farm gate, free for any of the villagers to take to ensure that nothing is wasted. There had been a charity collection box, but sadly even in this rural community, it was not beyond being stolen by thieves.

On discovering that our ‘medium’ goose had turned out a little larger than we’d expected Giles offered to halve it for us, sending us away with both it, the giblets for gravy making and the fat from our bird ready to render down for roasting - again making sure nothing goes to waste. We’ve still got half the goose sitting in the freezer, and I’m still roasting potatoes most weekends in that delicious fat for a super crisp and golden finish. Even from a butcher, I’ve never been given the goose fat as a lump before ready for me to do whatever I please, and usually in supermarkets the giblets (if they are included at all) are packed inside the bird in their own little plastic bag.

As a cook, our Longland bird afforded me a product where I had the chance to use the entire bird, and one which did not come with excess plastics as everything was wrapped in paper; Longland is a no plastic packaging operation, and when I asked if this was done for environmental or financial concerns I was surprised to hear that the answer was both. How often have we heard big producers complain that cutting down on plastic packaging will compromise their products? It turns out if your birds are not being thrown onto the back of a lorry tens deep, into a warehouse, and then onto supermarket shelves, paper is the only wrapping you really need. And, by not wasting any of my bird, I was given the opportunity to make sure that none of the resources that went into rearing it were wasted.

Indeed, Giles and Kate take pains to make sure that they are with their birds on every step of their journey to make sure everything is done to their exacting standards: they’re there when their birds hatch in the incubator, and the birds don’t leave the farm until they’re ready to be driven straight to the butchers and restaurants they supply - their on-site slaughter operation is not only convenient, but it also eliminates the stress and added environmental impact of a motorized journey at the end of their bird's lives.

By the way, the meat was exquisite, easily the best bird we’ve ever had at Christmas and a real testament to the difference getting a proper, field-reared, slow-grown bird makes. We’ll be eagerly anticipating both the goose half that remains in the freezer as well as next year's bird, because there is one practice at Longland that seems pretty alien among mass poultry and game producers across the west, and that is the practice of seasonality. We’re used to banging the drum for eating this way when it comes to fruit and vegetables, eagerly anticipating each spring’s crop of asparagus and the first early summer strawberries, but here in the UK, there are some farms that are ‘producing’ birds at a rate of about a million per day, ignoring that in the natural life cycle of these birds there is a season for new life: to satisfy our demand they’re forcing the issue.

Focusing on quality over quantity

That rough, ballpark, million-a-day figure explains why smaller producers like Longland have to focus on quality: it would be almost impossible to compete from a business point of view with those big supermarket suppliers for a mass-market product, so instead, something that is a luxury product (so-called because of the price point, rather than to buy into the idea that this is not the sort of duck we should be eating every time it arrives on our table: last year the trade price for one of their ducks was around the £20 ($25) mark - this year with skyrocketing prices for essentials such as electricity and grain feed, they have no idea what they’ll need to sell them for yet) where the very best of care has been taken at every stage is one of the few answers to a solvent business at this scale.

It does make you question how we’ve got to a place where we expect the price we pay for meat and poultry products - especially chicken - to be so low. British birds are a little pricier than average due to our high minimum wage and the cost of fulfilling our relatively high basic animal welfare standards. But why, then, in a race to the bottom for the cheapest price possible are we happy to import and eat birds that are not held to our own rigorous standards of care for both the humans and animals involved, adding food miles to a product we already produce copious amounts of here at home?

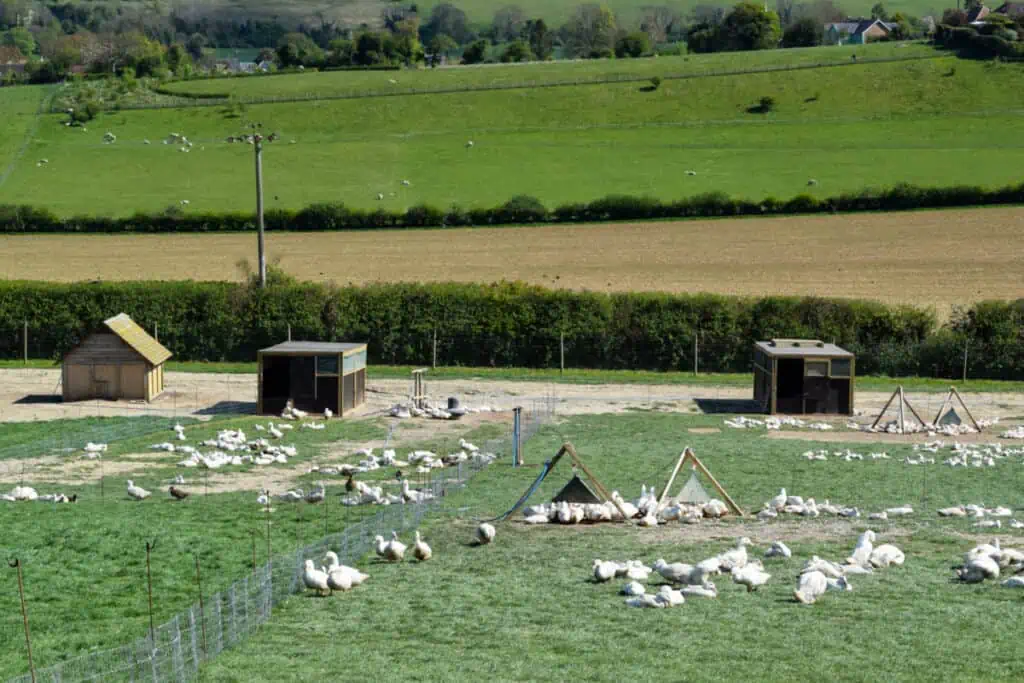

Asking Giles and Kate about scaling their business, I got the impression that whilst they had a little more field space to expand into, they’re content for now keeping things small as they focus on figuring out the best way to usher these birds through their lives. They showed me their new outdoor ventilated shelters they’ve constructed to help get their ducks outside at a younger age, but still protected from the elements; only adult feathers are waterproof, so for the younger ones, getting wet and catching hypothermia when the temperature drops at night is of real concern. I was a little irked to hear that this was the age many large commercial farms slaughtered them for the table, at 7 weeks old, rather than at the 12-16 weeks Longland prefers.

But should we really be eating ducks and geese in the first place?

I was also impressed by their system of movable fences meaning they can easily pick up and move everyone once they’ve exhausted their supply of grass, allowing the ducks to enjoy fresh grass, and for the land to recover. But, all of these positive signs aside, it is impossible to avoid the question of if we should be slaughtering and eating these birds in the first place? Can a farm really go far enough in replicating a creature's natural habitat to the extent where they live just as a fulfilling life as they would have done in the wild up until the moment of slaughter? But on the other hand, is farming livestock, poultry, and game birds something that can serve as an essential part of a regenerative farming strategy?

Like many of the questions surrounding the consumption of meat, I think this has to be a question for the individual.

Another innovation at Longland is the sprinklers they have available in each field allowing for the ducks to bathe and play in the water without big open bodies of the stuff which from a practical level would become a mud bath pretty quickly, but which would also help spread disease - ducks, of course, don’t know the difference between drinking water and bathroom water. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), a recognized benchmark organization for UK animal welfare concerns believes the law should be changed to outlaw this practice: they state on their website that ‘we believe that, as ducks are waterfowl, they should be provided with full-body access to hygienically managed open water sources that enable them to carry out their natural water-related behaviors, such as preening and head dipping.’ It is Longland’s position, however, that sprinklers allow the birds the same effect as they’re able to wash their eyes, without the risks created by open water. It is a question worth considering, and whilst work needs to be done to bring animal welfare to the highest standards possible within a carnivorous agricultural framework, what animal welfare organization is ever going to be happy with how animals and birds are raised for eventual slaughter? Motive is a little considered factor that should be acknowledged when we’re seeking information sources about what we’re eating. Personally, I don’t know the perfect answer.

I’m never going to quit eating meat even as I try to seriously cut down on my consumption to both improve my own diet and to be kinder to the environment. A perfectly cooked, juicy steak from a slow-reared Aberdeen Angus, or a perfectly pink duck breast from a Longland duck with a crisp, golden layer of fat on top is just too tempting.

But visiting the farm to meet this year's cohort of ducks has helped me refine the type of meat eater I want to become. My father has a car sticker supporting local farmers with the slogan: see the Red Tractor (a British food standards certification that refers to animal welfare and slaughter standards) and know what you’re eating. I’d take the concept a step further: find out who reared your dinner, how they reared it, and why (as well as producing a quality product, I want the people involved to care about doing the very best they can - for both the animals in question and the planet we all inhabit - at every single step of the process) and know what you’re eating.

Comments

No Comments